Tags

AFAB, autism, BACB CEU, behavior, behavioral seismology, cusp emergence, Cusp Emergence University, Dr. Kolu, ethics ceu, health, hormones, mental health, neurodiversity, PCOS, perimenopause, PMDD, PME, PMS, supervision CEU, trauma

Article in series on TIBA (trauma-informed behavior analysis) by Dr. Teresa Camille Kolu, Ph.D., BCBA-D

For many people including up to 90% of autistic women, our behaviors, moods, and medical symptoms worsen every month in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. But why? This may baffle even the most highly trained OBGYNs and behavioral scientists, let alone parents, caregivers, staff, and clients receiving behavioral services.

To Dr. Kolu, behavioral seismology is the scientific study of cyclical changes in a person’s experience that result in predictable (and potentially damaging) disruptions in an individual’s behavioral environment. Predictions about cyclical needs could be used to reduce the risk of damage and injury to clients and others related to hormone-behavior interactions. People can experience an increase in behavior needs, emotional needs, medical needs, and challenging interactions between all three, but it can help to know and be able to predict when they will be most at risk.

For individuals assigned female at birth (and relevant to anyone who loves, cares for, or conducts behavioral support for someone with these characteristics) , Dr. Camille Kolu discusses these four distinct behavioral risk profiles as ways to help make sense of the predictable disruptions that can occur regularly and monthly for up to 2 weeks at a time (as in PMDD) or for several years (as in perimenopause). The 4 risk profiles include the following:

- PCOS or polycystic ovary syndrome

- PMDD or premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- Perimenopause and

- PME (premenstrual exacerbation).

These 4 profiles are each accompanied by a pdf fact sheet downloadable as a resource in the new course on Behavioral Seismology from Cusp Emergence University. In each PDF are characteristic risk factors; biological signs; medical, behavioral and other symptoms the risk profile makes more likely; a to-do list for providers; and notes on expected interactions between behavior and the medical diagnosis. For instance, in PCOS, a client in behavioral services might experience self-injury related to the predictable pain during ovulation or food related behavior challenges that are related to the characteristic insulin resistance. In PMDD, a client in behavioral services who also has autism might experience sudden explosive outbursts in the second half of their menstrual cycle.

What are some of the benefits of becoming a healthcare or behavioral provider more informed about behavioral seismology?

Information can help to demystify behavior needs, as we put them into the context of an individual suffering with medical issues that need treatment. As a case example, one of Dr. Kolu’s patients had a diagnosis of PCOS (polycystic ovary syndrome) and took related medication. However, the behavioral team thought of that diagnosis as completely divorced from their behavioral treatment, and had never been trained on (or requested support to learn) what specific behaviors were anticipated and when they would get worse. As a result, the behavioral team had written goals that were inappropriate and inflexible. In most of the risk profiles we discuss in the Behavioral Seismology course, behaviors improve for the first two weeks of the cycle, when reinforcers are more potent. In the luteal phase of the cycle, a behavior targeted for reduction is likely to come raging back, as several things occur: one of the most significant is that aversive stimuli are temporarily more aversive! Another is that conditioning processes (such as extinction) are affected by hormone levels; for someone with trauma, the things we call “conditioned fear stimuli” or reminders of bad things that happened in the past, seem more present and potent during the luteal phase. Could these changes affect behavior? Absolutely! What if we ignored these biological realities and expected clients to simply do better and better on their goals in a linear trajectory? Could this be demoralizing for them and frustrating for caregivers and uninformed providers?

We can be more flexible in goal writing, more appropriate in support, more predictive in funding needs, and more compassionate in treatment, when we truly take someone’s medical needs into account. This is the point of the Behavior Analysis Certification Board (BACB)’s Ethics Code Item 2.12. For providers interested in taking that code seriously, Behavioral Seismology (4 CEUs total) provides an ethics CEU focused on treating behavior in ways much more contextually appropriate.

Other things you’ll find in the course:

- 4 pdf risk profiles

- An aversive stimulus tracker template (and filled out example)

- A Cyclical Needs Conversation Guide for providers

- A tool called “Rethink Your Language” (using the example of how the word “aggression” can cause impactful changes in someone’s life)

- Insulin Resistance Handout (with information about how this condition intersects with each risk profile discussed in the training)

- Information on how autism intersects in surprising ways with several of the risk profiles (and a tool called “Acting on Combined Risk”)

- A Cyclic Behavior Support Plan Template

- The Cyclic Systems Support Checklist (for companies and teams making these changes in their processes)

- A video script for the 8 videos accompanied by printable handouts

- Full references for over 70 published articles (including ones by autistic providers on lived experiences of individuals affected by both autism and hormone-behavior interactions

- Thought questions

- Thoughtful intersections and objectives to apply ethics codes to understanding the ethical implications of information in each chapter

- and much more.

Want to learn more? Take the course, contact Dr. Kolu to let us know you want to attend one of our live training sessions on Behavioral Seismology, or see the references below.

Behavioral Seismology References by Topic

Introduction to behavioral seismology:

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts. Copyright © 2020, BACB®, All rights reserved.

Beltz, A. M., Corley, R. P., Wadsworth, S. J., DiLalla, L. F., & Berenbaum, S. A. (2020). Does puberty affect the development of behavior problems as a mediator, moderator, or unique predictor?. Development and psychopathology, 32(4), 1473-1485.

Graber JA (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64(2), 262–269.

Negriff S, & Susman EJ (2011). Pubertal timing, depression, and externalizing problems: A framework, review, and examination of gender differences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(3), 717–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00708.x

References for PCOS:

Cherskov, A., Pohl, A., Allison, C., Zhang, H., Payne, R. A., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2018). Polycystic ovary syndrome and autism: a test of the prenatal sex steroid theory. Translational psychiatry, 8(1), 136.

Dan, R., Canetti, L., Keadan, T., Segman, R., Weinstock, M., Bonne, O., … & Goelman, G. (2019). Sex differences during emotion processing are dependent on the menstrual cycle phase. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 100, 85-95.

Dumesic, D. A., & Lobo, R. A. (2013). Cancer risk and PCOS. Steroids, 78(8), 782-785.

Evans, S. M., & Foltin, R. W. (2006). Exogenous progesterone attenuates the subjective effects of smoked cocaine in women, but not in men. Neuropsychopharmacology, 31(3), 659-674.

Evans, S. M., Haney, M., & Foltin, R. W. (2002). The effects of smoked cocaine during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle in women. Psychopharmacology, 159, 397-406.

Katsigianni, M., Karageorgiou, V., Lambrinoudaki, I., & Siristatidis, C. (2019). Maternal polycystic ovarian syndrome in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular psychiatry, 24(12), 1787-1797.

Mulligan, E. M., Nelson, B. D., Infantolino, Z. P., Luking, K. R., Sharma, R., & Hajcak, G. (2018). Effects of menstrual cycle phase on electrocortical response to reward and depressive symptoms in women. Psychophysiology, 55(12), e13268.

Sakaki, M., & Mather, M. (2012). How reward and emotional stimuli induce different reactions across the menstrual cycle. Social and personality psychology compass, 6(1), 1-17.

References for PMDD:

Browne, T. K. (2015). Is premenstrual dysphoric disorder really a disorder? Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 12, 313-330.

Ellis, R., Williams, G., Caemawr, S., Craine, M., Holloway, W., Williams, K., … & Grant, A. (2025). Menstruation and Autism: a qualitative systematic review. Autism in Adulthood.

Epperson, C. N., Pittman, B., Czarkowski, K. A., Stiklus, S., Krystal, J. H., & Grillon, C. (2007). Luteal-phase accentuation of acoustic startle response in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 32(10), 2190-2198.Ford, 2012

Freeman, E. W., & Sondheimer, S. J. (2003). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: recognition and treatment. Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry, 5(1), 30.

Gingnell, M., Bannbers, E., Wikström, J., Fredrikson, M., & Sundström-Poromaa, I. (2013). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder and prefrontal reactivity during anticipation of emotional stimuli. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(11), 1474-1483.

Halbreich, U., Borenstein, J., Pearlstein, T., & Kahn, L. S. (2003). The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28, 1-23.

Kulkarni, J., Leyden, O., Gavrilidis, E., Thew, C., & Thomas, E. H. (2022). The prevalence of early life trauma in premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Psychiatry research, 308, 114381.

Obaydi, H., & Puri, B. K. (2008). Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome in autism: a prospective observer-rated study. Journal of International Medical Research, 36(2), 268-272.

Protopopescu, X., Tuescher, O., Pan, H., Epstein, J., Root, J., Chang, L., … & Silbersweig, D. (2008). Toward a functional neuroanatomy of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Journal of affective disorders, 108(1-2), 87-94.

Sacher, J., Zsido, R. G., Barth, C., Zientek, F., Rullmann, M., Luthardt, J., … & Sabri, O. (2023). Increase in serotonin transporter binding in patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder across the menstrual cycle: a case-control longitudinal neuroreceptor ligand positron emission tomography imaging study. Biological Psychiatry, 93(12), 1081-1088.

References for Perimenopause:

Ambikairajah, A., Walsh, E., & Cherbuin, N. (2022). A review of menopause nomenclature. Reproductive health, 19(1), 29.

Arnot, M., Emmott, E. H., & Mace, R. (2021). The relationship between social support, stressful events, and menopause symptoms. PloS one, 16(1), e0245444.

Avis, N. E., Crawford, S. L., Greendale, G., Bromberger, J. T., Everson-Rose, S. A., Gold, E. B., … & Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. (2015). Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA internal medicine, 175(4), 531-539.

Constantine, G. D., Graham, S., Clerinx, C., Bernick, B. A., Krassan, M., Mirkin, S., & Currie, H. (2016). Behaviours and attitudes influencing treatment decisions for menopausal symptoms in five European countries. Post Reproductive Health, 22(3), 112-122.

Cusano, J. L., Erwin, V., Miller, D., & Rothman, E. F. (2024). The transition to menopause for autistic individuals in the US: a qualitative study of health care challenges and support needs. Menopause, 10-1097.

Duralde, E. R., Sobel, T. H., & Manson, J. E. (2023). Management of perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms. Bmj, 382.

Guthrie, J. R., Dennerstein, L., Taffe, J. R., & Donnelly, V. (2003). Health care-seeking for menopausal problems. Climacteric, 6(2), 112-117.

Hamilton, A., Marshal, M. P., & Murray, P. J. (2011). Autism spectrum disorders and menstruation. Journal of adolescent health, 49(4), 443-445.

Hoyt, L. T., & Falconi, A. M. (2015). Puberty and perimenopause: reproductive transitions and their implications for women’s health. Social science & medicine, 132, 103-112.

Karavidas, M., & de Visser, R. O. (2022). “It’s not just in my head, and it’s not just irrelevant”: autistic negotiations of menopausal transitions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(3), 1143-1155.

Kling, J. M., MacLaughlin, K. L., Schnatz, P. F., Crandall, C. J., Skinner, L. J., Stuenkel, C. A., … & Faubion, S. S. (2019, February). Menopause management knowledge in postgraduate family medicine, internal medicine, and obstetrics and gynecology residents: a cross-sectional survey. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Vol. 94, No. 2, pp. 242-253). Elsevier.

Moseley, R. L., Druce, T., & Turner-Cobb, J. M. (2020). ‘When my autism broke’: A qualitative study spotlighting autistic voices on menopause. Autism, 24(6), 1423-1437.

Moseley, R. L., Druce, T., & Turner‐Cobb, J. M. (2021). Autism research is ‘all about the blokes and the kids’: Autistic women breaking the silence on menopause. British Journal of Health Psychology, 26(3), 709-726.

Namazi, M., Sadeghi, R., & Behboodi Moghadam, Z. (2019). Social determinants of health in menopause: an integrative review. International journal of women’s health, 637-647.

Ohayon, M. M. (2006). Severe hot flashes are associated with chronic insomnia. Archives of internal medicine, 166(12), 1262-1268.

O’Reilly, K., McDermid, F., McInnes, S., & Peters, K. (2023). An exploration of women’s knowledge and experience of perimenopause and menopause: An integrative literature review. Journal of clinical nursing, 32(15-16), 4528-4540.

Pinkerton, J. V., Stovall, D. W., & Kightlinger, R. S. (2009). Advances in the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Women’s Health, 5(4), 361-384.

Pinkerton, J. V., & Stovall, D. W. (2010). Bazedoxifene when paired with conjugated estrogens is a new paradigm for treatment of postmenopausal women. Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 19(12), 1613-1621.

Polo-Kantola, P. (2011). Sleep problems in midlife and beyond. Maturitas, 68(3), 224-232.

Roth, T., Coulouvrat, C., Hajak, G., Lakoma, M. D., Sampson, N. A., Shahly, V., … & Kessler, R. C. (2011). Prevalence and perceived health associated with insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR; international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision; and research diagnostic criteria/international classification of sleep disorders, criteria: results from the America insomnia survey. Biological psychiatry, 69(6), 592-600.

Santen, R. J., Stuenkel, C. A., Burger, H. G., & Manson, J. E. (2014). Competency in menopause management: whither goest the internist?. Journal of women’s health, 23(4), 281-285.

Santoro, N. (2016). Perimenopause: from research to practice. Journal of women’s health, 25(4), 332-339.

Williams, R. E., Kalilani, L., DiBenedetti, D. B., Zhou, X., Fehnel, S. E., & Clark, R. V. (2007). Healthcare seeking and treatment for menopausal symptoms in the United States. Maturitas, 58(4), 348-358.

Wood, K., McCarthy, S., Pitt, H., Randle, M., & Thomas, S. L. (2025). Women’s experiences and expectations during the menopause transition: a systematic qualitative narrative review. Health Promotion International, 40(1), daaf005.

Zhu, C., Thomas, N., Arunogiri, S., & Gurvich, C. (2022). Systematic review and narrative synthesis of cognition in perimenopause: The role of risk factors and menopausal symptoms. Maturitas, 164, 76-86.

References for Behavioral Perspectives on Topics in Hormones and Behavior:

Altundağ, S., & Çalbayram, N. Ç. (2016). Teaching menstrual care skills to intellectually disabled female students. Journal of clinical nursing, 25(13-14), 1962-1968.

Ballan, M. S., & Freyer, M. B. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder, adolescence, and sexuality education: Suggested interventions for mental health professionals. Sexuality and Disability, 35, 261-273.

Barrett, R.P. Atypical behavior: Self-injury and pica. In Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics: Evidence and Practice; Wolraich, M.L., Drotar, D.D., Dworkin, P.H., Perrin, E.C., Eds.; C.V. Mosby Co.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2008; pp. 871–885.

Carr, E. G., Smith, C. E., Giacin, T. A., Whelan, B. M., & Pancari, J. (2003). Menstrual discomfort as a biological setting event for severe problem behavior: Assessment and intervention. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 108(2), 117-133.

Edelson, S. M. (2022). Understanding challenging behaviors in autism spectrum disorder: A multi-component, interdisciplinary model. Journal of personalized medicine, 12(7), 1127.

Gomez, M. T., Carlson, G. M., & Van Dooren, K. (2012). Practical approaches to supporting young women with intellectual disabilities and high support needs with their menstruation. Health Care for Women International, 33(8), 678-694.

Holmes, L. G., Himle, M. B., & Strassberg, D. S. (2016). Parental sexuality-related concerns for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and average or above IQ. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 21, 84-93.

Jain, N. (2024). Effect of hormonal Imbalance on mental health among young women.

Klett, L. S., & Turan, Y. (2012). Generalized effects of social stories with task analysis for teaching menstrual care to three young girls with autism. Sexuality and Disability, 30, 319-336.

Laverty, C., Oliver, C., Moss, J., Nelson, L., & Richards, C. (2020). Persistence and predictors of self-injurious behaviour in autism: a ten-year prospective cohort study. Molecular autism, 11, 1-17.

Mattson, J. M. G., Roth, M., & Sevlever, M. (2016). Personal hygiene. Behavioral health promotion and intervention in intellectual and developmental disabilities, 43-72.

Moreno, J. V. (2023). Behavioral Skills Training for Parent Implementation of a Menstrual Hygiene Task Analysis. The Chicago School of Professional Psychology.

Rajaraman, A., & Hanley, G. P. (2021). Mand compliance as a contingency controlling problem behavior: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 54(1), 103-121.

Richman, G. S., Reiss, M. L., Bauman, K. E., & Bailey, J. S. (1984). Teaching menstrual care to mentally retarded women: Acquisition, generalization, and maintenance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 17(4), 441-451.

Rodgers, J., & Lipscombe, J. O. (2005). The nature and extent of help given to women with intellectual disabilities to manage menstruation. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 30(1), 45-52.

Shors, T. J., Lewczyk, C., Pacynski, M., Mathew, P. R., & Pickett, J. (1998). Stages of estrous mediate the stress-induced impairment of associative learning in the female rat. Neuroreport, 9(3), 419-423.

Wegerer, M., Kerschbaum, H., Blechert, J., & Wilhelm, F. H. (2014). Low levels of estradiol are associated with elevated conditioned responding during fear extinction and with intrusive memories in daily life. Neurobiology of learning and memory, 116, 145-154.

Veazey, S. E., Valentino, A. L., Low, A. I., McElroy, A. R., & LeBlanc, L. A. (2016). Teaching feminine hygiene skills to young females with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Behavior analysis in practice, 9(2), 184-189.

References for Conclusions (Menstruation as a Vital Sign; Insulin Resistance and Hormones; Premenstrual Exacerbation)

Akturk, M., Toruner, F., Aslan, S., Altinova, A. E., Cakir, N., Elbeg, S., & Arslan, M. (2013). Circulating insulin and leptin in women with and without premenstrual disphoric disorder in the menstrual cycle. Gynecological Endocrinology, 29(5), 465-469.

Diamanti-Kandarakis, E., & Christakou, C. D. (2009). Insulin resistance in PCOS. Diagnosis and management of polycystic ovary syndrome, 35-61.

Eckstrand, K. L., Mummareddy, N., Kang, H., Cowan, R., Zhou, M., Zald, D., … & Avison, M. J. (2017). An insulin resistance associated neural correlate of impulsivity in type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One, 12(12), e0189113.

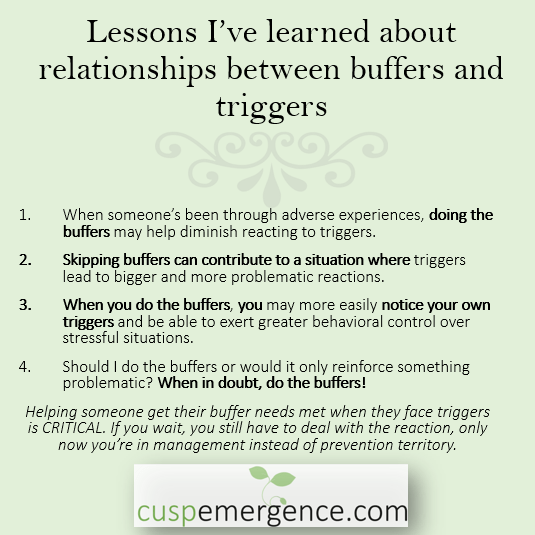

Kolu, T. C. (2023). Providing buffers, solving barriers: Value-driven policies and actions that protect clients today and increase the chances of thriving tomorrow. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1-20.

Kuehner, C., & Nayman, S. (2021). Premenstrual exacerbations of mood disorders: findings and knowledge gaps. Current psychiatry reports, 23, 1-11.

Lin, J., Nunez, C., Susser, L., & Gershengoren, L. (2024). Understanding premenstrual exacerbation: navigating the intersection of the menstrual cycle and psychiatric illnesses. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1410813.

Sullivan, M., Fernandez-Aranda, F., Camacho-Barcia, L., Harkin, A., Macrì, S., Mora-Maltas, B., … & Glennon, J. C. (2023). Insulin and disorders of behavioural flexibility. Neuroscience & biobehavioral reviews, 150, 105169.

Ueno, A., Yoshida, T., Yamamoto, Y., & Hayashi, K. (2022). Successful control of menstrual cycle‐related exacerbation of inflammatory arthritis with GnRH agonist with add‐back therapy in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 48(7), 2005-2009.

Vollmar, A. K. R., Mahalingaiah, S., & Jukic, A. M. (2024). The Menstrual Cycle as a Vital Sign: a comprehensive review. F&S Reviews, 100081.

Yu, W., Zhou, G., Fan, B., Gao, C., Li, C., Wei, M., … & Zhang, T. (2022). Temporal sequence of blood lipids and insulin resistance in perimenopausal women: the study of women’s health across the nation. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, 10(2).