Tags

autism, barriers, buffers, buffersandbarriers, children, cuspemergence, CuspEmergenceUniversity, family, kids, motherhood, parenting, parents, TIBA, trauma-informed behavior analysis, triggers

Another article in the TIBA series by Dr. Teresa Camille Kolu BCBA-D

In Chapter 8 of our course on Trauma Sensitivity, we cover the concept of “triggers” and what we can do about them. We cover this mostly from a responsive perspective in the course and use the following operational definition: “Triggers are historically meaningful stimulus complexes or relations between them. In their presence, behaviors or response patterns may be temporarily more likely to occur.” We continue with the big idea from Chapter 8 of that course, “One of the most supportive actions we can take is to stay mindful and do what needs doing in the moment”.

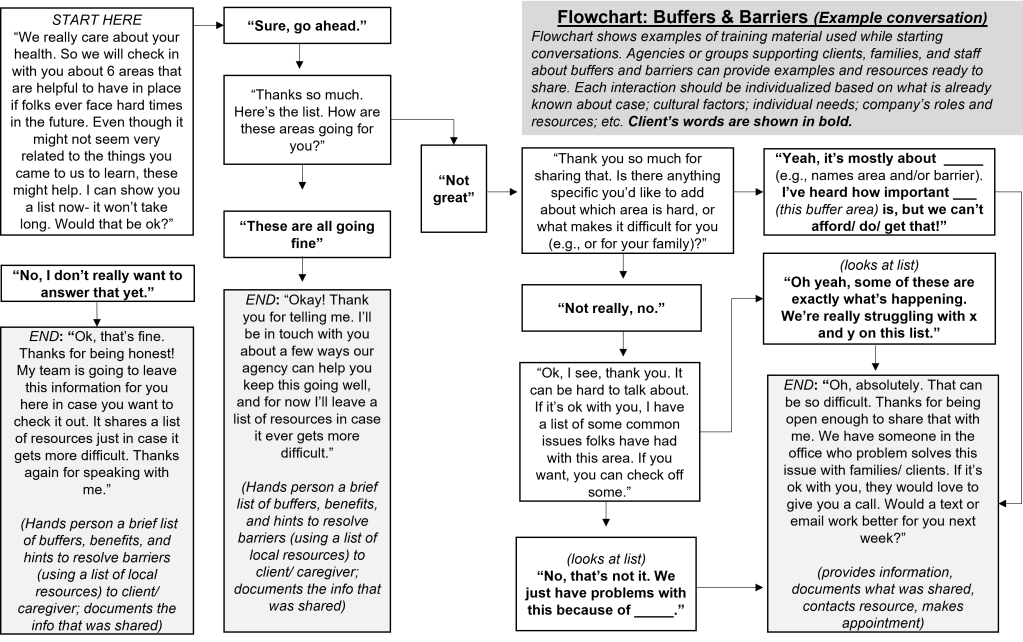

However, another huge thing we can do in helping someone through those triggering events or moments is to plan ahead. Below are some questions we ask our clients and their family members to answer, if they are interested in exploring this. Read on if you’re interested in some examples (we share a brief example of a dyad’s answers, where one member is the 5 year old kid, and the other is a parent). (Oh, and it may be helpful to check out the IPASS (find it in our RESOURCES tab)- this is a little tool we use for folks to go through their sensory environment for clues about triggers, if they need somewhere to start.)

Questions:

1.Name a person you love or a primary relationship you care deeply about.

2.Name an action that you do that shows compassion with them.

3.Name some things the person also does… that REALLY get under your skin.

4.Name an environmental situation or trigger that happens right before it is HARDEST to keep your cool.

5.List some things you start to notice when you’re feeling about to blow up/ lose your cool/ start doing actions that are inconsistent with your values to that #1 person.

6.State things you do to calm down in those moments that REALLY work or are most likely to work.

7.If you DIDN’T act to calm down and things kept getting worse, state the action(s) you would be likely to use next in the presence of that person.

Growth statement: Write your plan to prevent the triggers (3 and 4 above) from leading to actions that are inconsistent with your values (e.g., 7), by doing (6) as soon as you begin to notice things about your insides or the outside environment (5).

Ready to see this in action? Below are some parent answers. Keep in mind that neurodivergent parents often have neurodivergent children (or, looking backward, that neurodivergent children often have neurodivergent parents, whose qualities might not be appreciated until later, in the context of exploring diagnoses with their own children). Have you ever seen a mom struggling with her own misophonia exactly at the same time her child uses loud repetitive noises? Talk about triggering (for and to each other)! But stay hopeful and in the moment, because as hard as it is to be the thing in your loved one’s environment that sets them off, it’s lovely to be the person in their environment who can really understand where they’re coming from.

Parent Example: Answers to 7 questions, above

1.I love my kids.

2.I love it when I am able to use kind words and a calm voice with them.

3.Sometimes my kid makes repetitive noises, does not listen or interrupts me, or doesn’t follow instructions.

4.It is most difficult to keep my cool with my kids when I’m running late somewhere and my kid is not following instructions or is not doing something the “right” way.

5.I start to notice my face getting hot, my neck and face muscles are strained, and my breathing is shallow and fast.

6.If I splash water on my face, relax my muscles, stop and hug my kid, and breathe deeply, it helps to calm me down in the moment.

7.If I skip that step above, I usually proceed to raise my voice and may even shout or say things I don’t mean (things that are not kind and compassionate).

Parent Growth plan: “When I’m late somewhere and it’s really noisy, it’s especially important that I start to notice when I’m using shallow breath, the noise around me is increasing, or I’m noticing everything “wrong” my kids do and nothing right they’re doing. Right then, before I talk to my kid, I need to immediately try some of my calming strategies I listed above.”

OK, now for the kid’s answers.

1.I love my mom and baby brother.

2.I love it when I am able to keep playing, share, have fun.

3.Sometimes my mom tells me to stop doing something I love or tells me how to do something better or my brother takes my stuff.

4.When mom yells or my brother takes my stuff or we have to leave my game or book, it is most difficult to keep my cool.

5.I start to notice my face getting hot, my movements are jerky, my chest hurts, and my breathing is fast.

6.If I hug my mom, splash water on my face, stop and do some jumping jacks and then sit and breathe, it helps to calm me down in the moment.

7.If I skip that step above, I usually yell, hit my brother, or shout “NO! I WON’T!”.

Growth plan my parents can help with: When I’m being asked to stop playing or to do something that interrupts my flow, notice when I’m breathing faster and having a hard time talking. You can help by giving me a hug, doing some jumping jacks with me, and sitting with me and helping me to breathe.

At this point, we ask the parent some meaningful questions to help them make sense of what we’re noticing. And often this is uncomfortable (but becomes exciting and doable) as they first think, “oh, but won’t we be reinforcing escalation?” No, we’re turning it off.

Parents or caregivers, did you notice…

-Whether your having a hard time makes it harder for you to help your other person with THEIR hard time?

-Whether your hard time perhaps CONTRIBUTES to their hard time?

-Whether your triggers are echoed by the ones that seem to affect your kid or client? (e.g., are you teaching your other person to struggle with the same thing you struggle with, without your meaning for this to happen)?

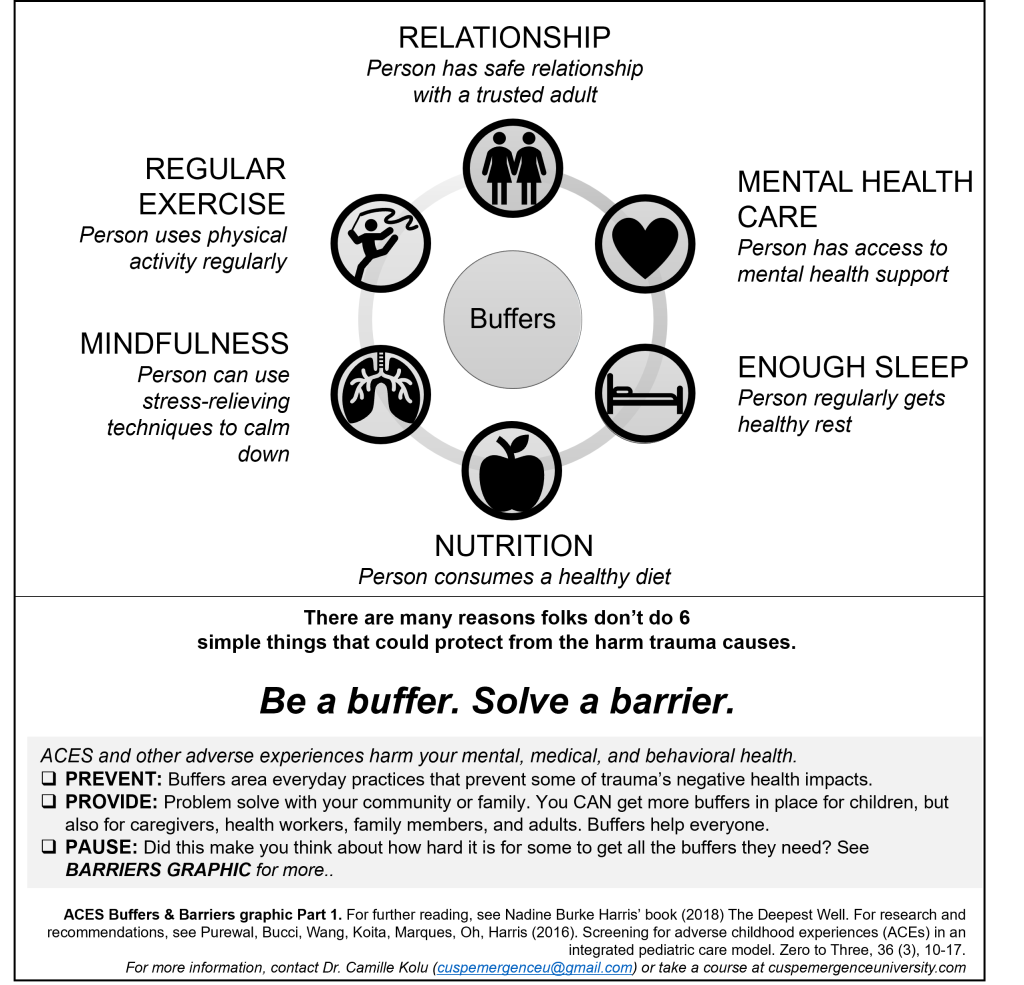

-Whether your triggers might be easier to manage at a period of time when you (or both of you) are well fed, rested, and exercised?