Tags

(An article in the TIBA series by Dr. Teresa Camille Kolu BCBA-D)

One day this spring, Dr. Camille of Cusp Emergence sat down to answer a few questions, and learn a LOT, from Enasha Anglade of LaughLoveLive Again. (You can learn more about Enasha and her work on Episode 87 of the Behaviour Speak Podcast!) Enasha and her fellow researcher and BCBA, Stephanie, talked with Camille about how Enasha’s company and work applies behavior analysis to supporting individuals affected by domestic violence. (And did we mention this dynamic duo will be presenting at BABA this weekend?! Go find them if you’re there!) We also discussed some of the barriers people face in this special context. Not all barriers can be solved with behavior analysis, of course, but there are many things we can do to insure we are minimizing the ones we know about, always staying open to learn about the client’s experience and special context. Each of the headers below reflects an important point heard from Enasha and Stephanie and some thoughts from a trauma-sensitive and behavior analytic perspective.

- First, be safe.

Interested in getting involved in working with this population? First things first: it’s really important to be safe for someone. This may seem like a no-brainer. In fact, providing a safe starting place for your therapy is where all trauma-informed support begins, even if (and especially when) your therapy is not treating the trauma itself, but solving problems or building skills or meeting needs related to it. However, there are so many ways behavior analysts violate this number one rule. We might do it unintentionally, such as when we go right to changing behavior instead of listening to a person’s experience and what they truly need first. While there are many trauma-informed resources out there on establishing safety and trust, you can also check out a course on building trauma-sensitive environments (starting with safety), or read a behavior analyst’s discussion on safety in Rajaraman et al.’s 2022 paper on trauma-informed applications of behavior analysis. But don’t skip asking the person how they feel safe and whether there are things you are doing or saying that contribute to their safety or their experience of danger. That’s right- behavior analysts can inadverdently present danger signals to our clients in many ways. When someone is in the middle of a dangerous situation, they are in survival mode and not ready to learn. We don’t want to trigger this for a client and we don’t want to make worse a situation that already exists for them. Being safe (and making sure our presence and therapeutic environment are safe) is not about helping clients avoid all aversive, challenging, or difficult circumstances. Our clients (especially in this context of domestic survivors) are already going through one of the difficult things in their lives. Coming for help and walking out of horrible situations may be even harder than what they’ve been through before… it will be unfamiliar, may be incredibly risky, and may occur at great personal cost to them. What they’re doing is brave. They’re already doing the hard thing. This is about taking their hand and really listening to what they’re going through.

2. Don’t be afraid to go there… but secure support for yourself so your client does not have to do the work for you

Speaking of listening to what they’re going through, behavior analysts can be bad at listening. Does that sound strange? Behavior analysts are great at observing, typically by nature and training… but we can learn to be better listeners, too. And it’s CRUCIAL in this work. Enasha notes that we are often afraid to be personal, to “go there” with our clients. For behavior analysts in the trenches of severe challenging behavior, we’ve often gotten our hands dirty, literally. But to understand our clients coming from domestic violence, being a witness to their story can be meaningful. Listen to your client. Listen long enough to hear. Listen enough to learn what they could benefit from, too. She may need a counselor recommendation, a connection to somewhere she can forge a meaningful relationship, or a tool that you can’t provide (but that someone you know, could). Their daughter may need help for something you don’t treat. Most important, listen to help your client, not just to facilitate your client’s progress with your program.

Related to “going there” with your client, make sure you are not a burden on THEM. If their issues trigger you, your session with them is not the time to discuss that. Of course, there’s nuance involved in learning to listen to someone, so it would be helpful to do any or all of these suggestions: secure your own therapist to go to if you are troubled; be prepared by using specific ACT and mindfulness techniques that keep you able to use your flexibility skills; help your staff debrief with pre-planned supportive interactions after difficult client visits; learn more about motivational interviewing (for a constructional approach from a behavioral perspective see Goldiamond’s constructional interview); and provide training for you and your staff from a trauma expert outside behavior analysis to answer questions about how to support someone disclosing difficult material).

3. Value relationship over rapport, but in the right way.

Your program isn’t everything. Behavior analysis doesn’t solve every problem (despite Skinner’s ideas about saving the world and articles by more contemporary well-intentioned behavior analysts interested in supporting human beings). But your relationship with your client might matter more than you think. And I’m using the word “relationship” instead of “rapport” on purpose. (This section could also be titled, “De-centering us, and behavior analysis, while putting a higher priority on that person and what they need”.)

Of course, if we were talking about real rapport, in the way the layperson uses the term rapport, we’d be talking about the same thing as relationship. The word rapport just means “a close and harmonious relationship in which the people or groups concerned understand each other’s feelings or ideas and communicate well”. But in behavior analysis, the word rapport typically connotes a more transactional process, one used as a procedure as a means to an end. Ultimately, many behavior analysts view rapport as a process one includes in the beginning of sessions or relationships with clients so that clients will be more likely to approach the instructor, and so that the instructor can deliver instructions, reinforcers and other environmental stimuli that encourage the client to change their behavior in specific ways the team has defined and prioritized.

Relationship viewed as an end is different. It has benefits beyond the program. It validates the person and prioritizes their needs. You might think of the way that with a relationship between two people who care about each other, we say goodbye when we’re done. We don’t just transfer off the case without letting the family know because we got a new job, or our hours were cut. However, we’re also not suggesting behavior analysts engage in dual relationships with our clients (an unethical and unhelpful practice to be sure!) What we’re really saying is to value the person over momentary instructional control, and treat them… well, like a person. We still need to be careful, and cautious, to preserve the integrity of precious boundaries. In other words, you are still not going to show up as your client’s “friend”, and you need to teach them, lovingly, how this will work in the beginning of your therapeutic relationship with them. You care about them, and you care enough to support them with their goals. That may include finding friends, or engineering environments that facilitate their making friends, but that’s not you; you’re the therapist. You can still be a good listener, care about your person, and support them without being their friend.

We can program toward the end the entire time, so that there is no disruptive surprise for the client at the ending of the relationship. I like to think about this as fading out interactions to a very low rate that is tolerable, and with programming additional sources of reinforcement for the client. Being the only person your client can trust wouldn’t be helpful; what if you were to have a car accident, move away, or have to reduce your hours? All those things happen, but if you plan from the beginning, you can insure they happen in more therapeutic ways. Be really careful to use ethics code guidelines on transferring cases, especially when you are working with someone in a sensitive and vulnerable situation like those surviving domestic violence.

4. Accept this: any behavior can be influenced both by its consequences in the moment, AND the relevant context and history.

When loud voices in the room ask “what does history have to do with behavior? Shouldn’t we just treat the function that’s controlling it now?”, it can be tempting for vulnerable behavior analysts to question themselves. Should I even be taking a trauma-sensitive approach? Should I take this person’s history into account at all? If it’s just paying off for them in the attention it produces, and we technically know about methods to turn behavior on and off using procedures based on consequences and arranging stimulus control conditions, what does it really matter?

Actually—in terms of bringing up trauma, or changing goals based on it—the answer may vary depending on what the client needs! CuspEmergence doesn’t recommend taking a trauma-informed approach when clients don’t need it. But those going through domestic violence all have been through trauma, by definition. As Rajaraman et al. (2022) states, “Responses to trauma may indeed vary from person to person; however, ACEs are well documented, and a preventative TIC approach would acknowledge their potential impact”.

We recommend behavior analysts working with survivors of trauma be intimately acquainted with the ways trauma relates to behavior, to medical needs, to subsequent challenges and needs, and to the barriers people face in moving on to healing circumstances. (See the sections nearer the end of this article for educating your team if that’s not your forte). And yes, behavior can be influenced by BOTH history (such as the trauma-related factors that were present when someone began to use behaviors that are now difficult for them and they want to change, even if those behaviors are NOW maintained by other environmental factors).

Because behavior is at any moment a function of the dynamic interaction between the local and historical context, it is possible that the intervention strategies identified during the functional assessment phase as “likely to be effective’ will need some modification when it is actually time to intervene. As Stephanie notes, clients affected by domestic violence may face unpredictable and changing needs. The needs of the client demand that the analyst be flexible and sensitive to the contingencies and challenges our client faces. We should be especially focused on tracking the ways we might be contributing (perhaps unintentionally) to coercive cycles of interaction for our client, perhaps hindering their growth by playing in to a power differential or offering choices using an architecture that WE don’t perceive as, but the CLIENT experiences, as coercive.

5. Identify the basic training your team will need. What are the most essential and meaningful training components your staff will need? Who provides that training, and how can you value it at the levels of culture, group, and individual?

What happens when most of the team cannot relate to the particular difficulties with which a client is struggling? They might recommend changes that are not feasible to the client; they might miss danger signals the client is sending based on what is happening around the client (and miss an opportunity to prevent harm); they might take personally or misunderstand the challenges a client is having and miss crucial chances to intervene appropriately; they might cause harm by actions intended to help; and so much more.

One team we know used to have a person on staff who provided this training because she had been through it, but her caseload is now too big for her to spend time with each new staff person. As the team grew, the personalized approach they were known for was eroded and eventually, the services they provided looked like most other agencies, and they were no longer meeting the individual needs of client families. However, they didn’t know it until they received feedback, because nothing had been intentionally changed; it was simply a product of drift that happened with the welcomed growth going on.

So one solution for teams with similar paths is to prioritize providing training from a reputable and experienced source, and doing that both routinely and in a way that continues to answer questions the new team members will have as they gain their own experiences and put their previous knowledge into their new context. In a subfield like domestic violence, this training needs to come from someone either outside of behavior analysis, or from someone whose training, expertise, experience and culture strongly intersects with that of the clients and their needs. If this person is not on staff, it is essential to secure regular training, as well as embedding this as a priority into the agency’s mission, core processes, values at work, and interacting with clients. Staff should not have to ask for designated and regular times they will be paid to access and discuss and apply the training (and receive appropriate feedback from someone equally experienced and trained).

6. Identify the most important kinds of support your clients will need that you cannot or do not provide. What kind of support is needed, who else provides it, and what would you like to be doing in 5 years if you removed barriers related to this support?

The first part (who else provides this?) is a logistics question. Prioritize finding those answers right NOW. If most of your clients receive behavioral support from you, but also need to be able to access certain other resources to survive, find out all about those resources and who provides them.

The idea is that you can position your agency in the middle of a network to which you can connect your clients. You do not want them struggling, alone, with something that could make or break their ability to come back to access your services or to implement them. We can start small, beginning with very simple connections you provide your client, such as a list of websites, phone numbers and connection names for partner agencies in your area that meet big needs (and funding options for those needs).

The second part (what would you be doing in 5 years if you removed obstacles?) takes more planning, but might make sense strategically depending on your clientele and their challenges. Some of the solutions could include creating a part- or full-time position of Resource Coordinator, hiring a social worker, or forging a strategic partnership with someone who fills this role for other companies and who knows your area well and can devote time to your own clients on a weekly or regular basis that makes sense for your client volume.

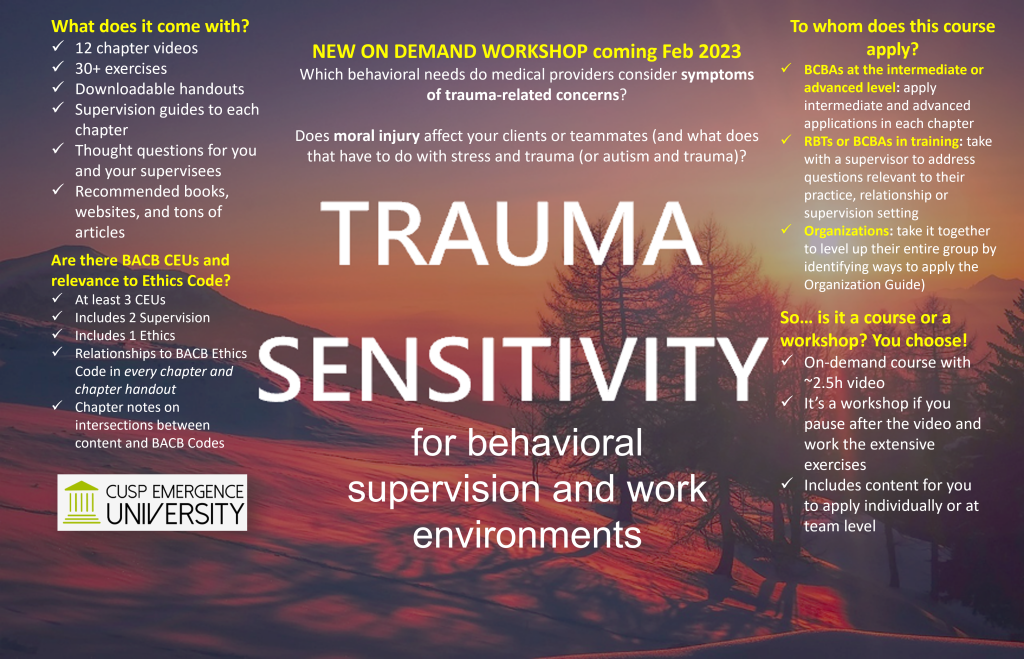

Do you do this work yourself? Contact us and add your essential strategies. Want to learn more? Find Enasha and Stephanie at BABA, listen to the podcast (Ben is in Detroit right now documenting BABA 2023!), follow ACES and ABA groups on social media, send us a comment and leave us your email below, or take a course on trauma sensitivity. We hope to hear from you soon!