Tags

beauty and the bug, beauty and the bug cusp emergence, ceu bacb, cusp emergence, ethics ceu, trauma, trauma and behavior analysis, trauma and developmental disability, trauma and ID, trauma-informed behavior analysis

Beauty and the Bug (in which we briefly explore trauma and non-neurotypical people, ask how to raise tender-hearted children, and see a bug portrait in pointillism)

This is the 15th article in a series on Trauma-Informed Behavior Analysis by Dr. Teresa Camille Kolu, Ph.D., BCBA-D.

How do we teach others to tend the needs of those who cannot express them (or for that matter, appreciate the lesson of loss, the tenderness of pain, the beauty in brokenness)? And how common is trauma in individuals with serious developmental disabilities? Many of us have not considered the relevance, let alone the prevalence. Is this because we can’t see it, don’t hear about it, or think that it is out of our scope to address? These questions occurred to me this week as I thought about a participant from a recent training I provided, who asked if the model of trauma-informed behavior analysis (about which I’ve been writing here) applied to individuals with intellectual differences (it does!). Even to us professionals in the field of behavior analysis, the complexity of and subtlety of trauma and behavior remains elusive.

This week my family lost a wonderful man. He and his wife tended to the needs of others (often before their own). Also this week, my reason for taking a work break turned three months old, and Imagine! (a nonprofit agency in my area) had its annual celebration. As I mulled over these questions about trauma and differences and on raising good people, a therapist friend posted Imagine’s video of one of their clients. I realized I had not blogged before specifically about treating challenging behavior in someone who is differently abled. I need to do that, lest one more reader think that this approach (trauma informed behavior analysis) is mainly useful for “vocal” clients, or those who can easily articulate their pain and past. Today, Shelly and her zany personality inspired me to do this.

Individuals with developmental and intellectual differences express or show their history and needs in different ways, and sometimes caregivers overlook the contributions and signs of trauma, neglect or even ongoing abuse. When we (especially behavior analysts) overlook these, we are not addressing the real reasons for challenging behavior, and we might miss the importance of connecting the person with critical mental health resources, or of offering a chance to heal past wounds. We know about functional communication training. But do we fully address subtle needs to communicate pain—both emotional and physical? And when someone lives in an environment or is exposed repeatedly to a situation or person that is aversive (even abusive!) do we teach them to effectively advocate for removal and communicate their discomfort, or do we merely try to reduce the “challenging behavior” that often accompanies the terrible situation? Do we recognize the signs of abuse in individuals who have few skills to communicate?

Too many times, I took a case where team members requested decreases in “challenging behaviors” in someone with diseases like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer, or Spina Bifida, before the team had recognized that the main thing challenging about the behavior was that it was going on because the individual had NO dignified way out. A conversation with a peer last week revealed that without training in these issues, a behavior therapist or even the entire team might treat “suicidal ideation” as a “behavior to be decreased” rather than a serious problem to be solved. (Even when this “behavior” is partly a habit the person has learned to use as a tool to produce needed attention from others, a whole behavior analysis of the situation would consider the risks and possible outcomes of addressing it in different ways, and document and address the related needs to understand and address why this was happening.)

As Shelly and her team alluded to in the video, the very state of not being able to communicate one’s needs and preferences can be traumatic in itself, and can lead one to develop desperate behaviors that just get called “behaviors for reduction” in the individualized behavior plans of thousands of clients. Today there are no more excuses for not helping someone access and master a communication system that works for them. To be sure, not everyone has access to a Smart Home residence decked out with all the tools we saw on the video- but have you seen the article on an accessible app developed by the brother of a man with autism in Turkey (so that he could communicate needs and gain leisure skills using only his smartphone)?

Tragically, many of my clients went through abuse and neglect and need someone to write careful and informed behavior plans that teach them skills they did not have at the time, like articulating emotional and physical pain, advocating for their needs, and requesting to be removed from a serious adverse situation. Just as important, these clients need an informed analyst who designs ways that these skills will persist when the client moves environments, as I found when a former client kept being exposed to new team after new team that didn’t read the plan and failed to recognize the communicative intent of the behaviors, and the medical component to the “challenges” the team demanded to be decreased. This calls for TIBA or trauma informed behavior analysis (if the team is not already using it).

So it’s not enough for our clients to learn these skills one time. The people who make up the audience, the environment, must respond enough to maintain them. If I ask for help and you respond no, why would I ask again? Remember the lessons of the family whose school team actually discouraged them from using “saying no” as a goal for their adolescent girl with autism, arguing that they didn’t have the resources to deal with her protesting all day long. Actually, the opposite is more likely to be true—that when our “no” is respected (listened to the first time), its use will be more limited to situations in which the person really “needs” it.

So back to my original questions. How do we raise little ones who are likely to grow up to appreciate and shape the voice of the voiceless, who honor the needs of people in ugly situations, who see the beauty in what others view as broken or beyond repair? How do we insure people will have the internal resources to value what isn’t immediately perceived as “valuable” by the culture? Maybe it starts when they are little, in modeling ways we can accord dignity to the frail, the elderly, the dirty. We cultivate tenderness as we show them we appreciate the spiderweb (AND the spider), the weed and its flower, the worm (thanks, mom and dad, Nicolette Sowder of wilderchild, and my very first client who taught me that not being able to talk is not the same as not having anything to say- click here to learn about Rett Syndrome).

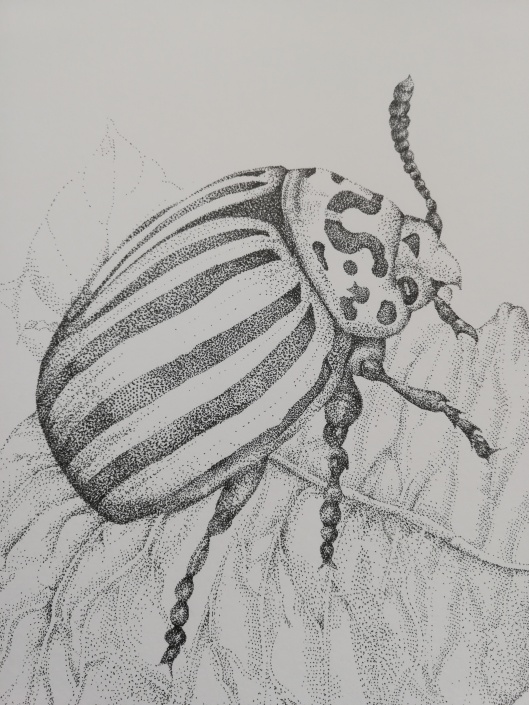

Thanks to mom and dad, I still notice bugs and their beauty. I thought this one was wonderful when I looked closely, so I spent even more time to study and draw him. I thought he became even more beautiful as I continued to look. Maybe you can see his beauty too.

Colorado Potato Beetle by Camille Kolu (c) 2018

P.S. There is so much trauma in our schools today, whether you work with students who are “typically developing/ neurotypical” or those with intellectual, developmental and physical differences. Don’t miss the next course from Cusp Emergence University on trauma informed behavior analysis in the educational setting (complete with CEU’s including one for ethics).

Some references and resources

Articles on prevalence of assault and ACES in individuals with developmental differences:

https://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/14/2/87.short

http://www.cfp.ca/content/52/11/1410.short

Read about Imagine! Smart Homes: https://imaginecolorado.org/services/imagine-smarthomes

Read about the man who developed an app for his brother: https://www.bbc.com/news/av/stories-47001068/how-brotherly-love-led-to-an-app-to-help-thousands-of-autistic-children

Get the full TIBA (trauma informed behavior analysis series): https://cuspemergence.com/tiba-series/

a

a